Today, we have something between a novella and a thesis. But Will Awdry is advertising royalty, familiar with the corridors of the esteemed Bartle, Bogle Hegarty, Leagas Delaney, Ogilvy, Big Fish and BDDH. So I let him wave at us from the back of his limo for an awful long time…

How did you get into the creative game?

How did you get into the creative game?

My greatest influence was my father. He had a novel published aged 23 and a theatrical review on the West End stage, with Hughie Greene and Gerald Harper, a year or two later.

Children started appearing. There are four of us, including we latter two mistakes, and he had to pay for us somehow. Novels and reviews weren’t going to do it. He took a job in advertising, adding pages to unfinished novels in his bottom drawer when no one was looking.

I suspect that’s when the noble rot of ‘this funny trade’, as he called it, seeped into my DNA. I had also had the Rev Wilbert Awdry as a distant relation. A writer and vicar with the voice of a mellifluous clarinet, he was often on parade at family weddings and funerals.

The Reverend’s Thomas the Tank Engine books were held up as an example of a broader inheritance that we might be able to write something.

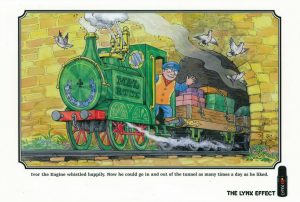

I did once try and squeeze the Fat Controller into an inuendo-laden Lynx/Axe print campaign that Rosie Arnold and I dreamt up, but we were slapped down by the publisher’s lawyers on grounds of offensiveness to children. We fell back on Ivor the Engine instead.

After a cloistered, posh education, I left school aged 17 and wandered around South East Asia, letting time even out the age disparity from my peers. A subsequent geography degree from Oxford, punctuated by holiday spells as a lavatory cleaner, completed academic life.

After a cloistered, posh education, I left school aged 17 and wandered around South East Asia, letting time even out the age disparity from my peers. A subsequent geography degree from Oxford, punctuated by holiday spells as a lavatory cleaner, completed academic life.

Various careers beckoned but, recklessly, I ran away to sea. Aboard a (very) rich man’s plaything, I completed the crew of four women and eight men as a deckhand, piloting 148 feet of gleamingly expensive metal across the Atlantic.

We trundled up and down forty or so Caribbean Islands for a season. On the way back, I wrote my resignation letter 1500 miles from land and then went through the worst storm of the trip, south of Saint Tropez. All the legs broke on the grand piano.

Pausing on the way home in Montreux, Switzerland to appreciate wavy mountains rather than mountainous waves, I returned to London looking for a job.

Pausing on the way home in Montreux, Switzerland to appreciate wavy mountains rather than mountainous waves, I returned to London looking for a job.

Advertising seemed a logical next step. I wangled interviews at Fletcher Shelton Delaney, Reeves Robertshaw Needham and Abbott Mead Vickers, before the singularly named McCormick’s took a chance on me as an account trainee.

My first day, I drank four pints at lunchtime at my mentor’s insistence. The next, an account director in the same restaurant where I was being introduced to a client sent back the bill because it wasn’t expensive enough.

My first work challenge was to find and purchase a stuffed parrot. Over the months to come, I learned more about bladder control, expense claims and whimsical management demands.

The agency phone list was peppered with fantastically beautiful women, clubbable but childish blokes, some driven, managerial people and a smattering of genuine talents.

I hated the fact that, whenever anything good happened, the creative department took the credit and, whenever anything went wrong, account management copped the blame.

Working out these frustrations by hitting drums in the agency band, I attracted the attention of Gerry Moira. Gerry was the singer. There was a period where you couldn’t attend a London advertising function without dancing to the Stevie Cook Soul Band.

Gerry’s voice melded (and still melds) both Dan Ackroyd and John Belushi in a commanding, Blues Brothers rasp. He also just happened to be the creative director.

It was he who agreed to let me transition to copywriting by working out my notice in the creative department. Teaming up with David Meldrum, a promising art director from Ireland, I left McCormick’s on Christmas Eve, 1985.

Bartle Bogle Hegarty had just won the Asda business. We delivered our ‘book’ to Graham Watson. He showed it to Hegarty. We started at BBH, in the basement of their Frith Street offices, on 13th January 1986.

Within six months or so, John rejigged things and partnered me with another art director, Martin Galton. There began nine years of working with the funniest and most inventive individual you could wish to meet.

We were allowed four weeks to produce press campaigns, six to generate TV work. In the first year, we recorded dozens of radio commercials, developing nodding acquaintances with a curtain call of admirable actors.

Besides Asda briefs, we grabbed every opportunity going: Audi, Whitbread, Sony, BT and, after several attempts, Levi’s.

We were lucky. We won some awards. The culture of success bred incredible confidence. Everyone wanted to be – and to do – the best, but we had an awful lot of fun doing it.

How did you gravitate to being a creative director or partner?

There isn’t a set path from copywriter to creative director, far less one that will gather you respect and success. All those tropes about ‘those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach,’ stand as a warning. Any fool can be a creative judge – aren’t we all? – but precious few can actually direct and build.

Gerry Moira, John Hegarty and Barbara Nokes gave me on-the-spot lessons in how to steer people to better places. Regular trips to D&AD evening sessions at various agencies added to my understanding.

During those workshops, I learned most from the people who were hopeless at running them. Some of the stellar creative names of the time ranked amongst the worst communicators I had ever met.

In the years since, I’ve also learned to be careful of creative directors who grab the magic marker or the mouse to show you what they’d do and how they’d do it. That’s not creative direction, it’s creative dictatorship.

My elevation came about by asking John Hegarty if I could take on the responsibility. He looked doubtful but granted my wish. I started piloting an account or two.

The accelerator hit the floor when we launched BBH Unlimited, a one-stop, integrated outfit cradled within the main agency but – ostensibly – a stand-alone affair. Our big client was Audi.

I made some terrible decisions and, quite rightly, received the full dressing-down from John in a stinging, savagely accurate email.

But we also engineered Audi’s Wakeboarder TV ad into being. Danny Kleinman shot Al Welsh and Nick O’Brian Tear’s script on the same beach where they filmed The Piano, in New Zealand. The ad ran in 72 countries.

I also was able to recruit stellar people. Andrew Jolliffe was a standout copywriter, an improbably angular man with a life story that read like a John Buchan novel. He remains a true friend.

Richard Exon joined us from BBH account management and was the life, soul and ballast of the project. Heather Alderson kept Planning’s head high throughout and the indefatigable Steve Kershaw drove us all with good-humoured urgency. Ali Augur, one of the best designers I’ve ever encountered, became our graphic conscience.

With long anguishes of impostor syndrome, I creative-directed BBH Unlimited and a few agency accounts and then went on to ECD at Partners BDDH. We topped the new business league, but they wanted an iconoclast, not an acquiescent geography teacher.

At DDB, in the Boase Massimi Pollitt building in Paddington, I tended some international accounts for three happy years, particularly Unilever’s Knorr. One of Rotterdam’s gems, the brand was selling $2.2 billion worth of stock cubes across fifty or sixty countries.

Before the word ‘story’ had become appropriated by legions of advertisers, we gave them ‘Every meal is a story’ as an overall, unifying thought. Ogilvy and Mather then waved at me and I travelled east for eight strange years, creative directing the Campaign For Real Beauty for Dove (for Unilever again), BP and SC Johnson.

I learned about the weird cult of global holding companies, Martin Sorrell (always very supportive) and doing advertising in the Truman Show setting of Canary Wharf. Latterly, I’ve had five rejuvenating years creating, or re-infusing, food and drink brands at Perry Haydn-Taylor’s design consultancy, Big Fish.

Energetic entrepreneurial clients, speed, agility and exceptional creative talent were all mashed together in a bullshit-free studio, more like a kitchen than a workplace. I loved it.

Several paragraphs on, this doesn’t really answer the question of ‘gravitate’ to creative directorship. I suppose the simplest answer is that, after I asked John Hegarty if I could have a go, I spent my time falling forwards without making much of a plan or impression.

However, I didn’t fuck it up completely either. Creative directorship just happened. I didn’t get killed – though I’ve been made redundant a couple of times – and I’m not sure that I’ve ever been that good at the job. That’s being honest, not modest.

And for those who haven’t been brought up in agencies, can you tell us how the roles differ?

When I first arrived in advertising, as a naïve squit, I thought everybody did more or less the same job. Very quickly, I learned of the battle lines that existed between account management (bankers) and the creative department (artists).

The divide was as absolute as the Iron Curtain. It was only much later that I realised the distance between the two is far shorter than convention suggests.

At a broad level, the three main roles in agencies lean on different skills. Account management demands realism and suits facilitators, connectors, communicators and organisers.

The creative people are there as generators, fantasists, pathfinders and articulators. They will produce work of much greater depth and impact if they have the support of planners (or strategists) who, in turn, are audience readers, water diviners, stimulators, provocateurs and summarisers.

There is also a critical fourth skill, which belongs to the make-it-happen people. This group are the producers and builders of whatever it is the agency creates.

As a copywriter, you can either play with the proposition that a strategist has put on a convenient spot for you to kick around or, more usefully, bring a stand-alone strategic thought into play simply by the way you write to your audience.

What’s going to motivate the reader or viewer? Why should they care? Unless you can conjure up an imperative or compelling reason to attract their attention so they retain your message, your writing will go unread and, worse, unremembered.

By that yardstick, every writer has to generate a motivating idea. (A student in a recent writing class of mine defined an idea as ‘a sail that catches the wind’.) You can write your way to a compelling proposition quite swiftly if, as Americans say, you simply write everything down ‘from the get-go’.

You will almost always find a gem somewhere on the page. With any luck, in your own words, a ‘truth well told’ will jump out at you. In my book, therefore, copywriters are strategists too.

As a creative director, some of your best work is done away from the ball. Deciding which teams or individuals are right for a task demands a proper, intuitive understanding of your people.

Fashioning and tailoring briefs with both your clients and your management teams in advance will ensure you’ll be asking for creative work that addresses the right exam question.

Keeping all conversations around the brief going while your writers, art directors and designers are actually tackling it will keep the thinking alive and sell the results further down the line.

When you’re managing and steering creative people, it’s important to acknowledge how fallible you are but, nevertheless, give them clear, decisive feedback. Simply telling them that you don’t like what you see or that the work isn’t good enough falls woefully short.

If you’re going to break their efforts into small pieces, killing their offspring in front of them, you have to provide a route onwards from where they are now. It might be a restart or a leap forward. It’s vital that you then give them enough space to make the work not only their own but, more importantly, to make it better.

Do you miss the pure writing role?

I probably talk more about writing than I actually write, but I’m lucky to be able to do a bit of everything. I’ve written two books in the last two years, one about Wembley Park and its development and the other, a history of Macallan whisky.

Some of the Big Fish food and drink brands that I helped write into existence are only reaching markets now, while others are going from strength to strength.

I have both a copywriter’s and a creative director’s life with Sutton Young (a design business that specialises in property) and Beehive (a virtual ad agency). To keep me on my writing toes, I also coach Writing for Advertising courses at British Design and Art Direction.

That’s meant running day-long workshops for more than 1200 people in the last few years. Additionally, I have one or two other pursuits that involve scribbling away.

Any overspill falls into a very self-indulgent blog. It’s a tad more interesting than the diaries of my youth (‘Porridge for breakfast. Mucked about in afternoon.’) but the readership remains in single figures.

Who’s been your greatest teacher?

John Hegarty taught me the most about good advertising. You could leave his office with your pad on fire and your soul crushed, but you knew exactly what you had to do and where you had to go, using your words, not his.

His wisdom and energetic positivity were infectious. In the same breath, I have to mention Nigel Bogle. A (sometimes terrifying) beacon of decency, intellectual probity and diligence, his approval was hard-earned but incredibly satisfying.

His tough love, blended with John Bartle’s insightful humanity, meant that my real teacher was Bartle Bogle Hegarty, the agency. Until I began working there, I’d facetiously characterised advertising as ‘Second-rate people having a first-rate time doing a third-rate job’. At BBH, it was first, first and first.

I’ve also learned from the art directors I’ve worked with. I’ve mentioned Martin Galton.

I can’t not mention Rosie Arnold too. We spent six wonderful years together. Advertising royalty, she is a peerless pioneer of inventiveness and one of my life’s happiest associations.

At Leagas Delaney, I was teamed with the remarkable Dave Dye and then, all too briefly, the luminous genius, sadly no longer with us, that was Gary Denham. He had the best eye for beauty of anyone I ever encountered.

You handled some big accounts at Ogilvy and Mather. What was your finest hour there?

An hour is made up of many minutes. I don’t think there was one, single moment of great triumph at Ogilvy and Mather from a personal point of view, but there were some highpoints.

I took over creative-directing Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty in 154 countries from Dennis Lewis. It was a ridiculously large playing field and I barely covered a square inch. There were other creative people, performing outstandingly, across the globe.

Notionally under my aegis, Janet Kestin at Ogilvy, Toronto, creative-directed ‘Evolution’ into being, the double Cannes Gold-winning film by art director Tim Piper. At the same time, I was proud to be helping a brand that organised over 600,000 workshops for young women to promote their sense of self-esteem.

With my joint creative lead, Alasdair Graham, we managed to convince Andy Bird to join as an art director and partner the exceptional copywriter, Sue Higgs. (Her 2020 posts about bullying are harrowing, depressing and sadly necessary. Look them up.)

I did a bit of housekeeping around one project that Andy brought to life, which was an anti-homophobia-in-football spot for Kick It Out. To him go all the honours, but I had an administrative and pitch winning fingerprint or two in there somewhere.

Working with BP globally, as an enormous hydrocarbon energy provider, was not without controversy. I was simultaneously creative-directing WWF’s work, which became trickier when the Deepwater Horizon disaster happened.

The BP marketers were actually a very decent bunch of people and their sponsorship of London 2012, the advertising we produced, and the overall experience made for some very special moments, even if we didn’t hit stratospheric creative heights.

We were able to hire a student creative team directly from Lincoln in Daz Urquhart and Tom Smith, now hugely celebrated in New York as creative directors. They developed all the Olympics work. Their rapid progression to becoming heavy hitters was a joy to watch.

Finally, and luxuriously, I was able to visit the Ogilvy chateau, Touffou, near Poitiers, as a coach to WPP graduates in their first three years of rotation through WPP agencies.

Herta, David Ogilvy’s widow, has made it her life’s work to bring the 11th-century French castle to life. It is an incredible place.

Thanks to Jon Steele, the worldwide planning director of WPP, I was transported there three times with different groups of graduates, for sleeplessly breathless visits of a few days while the WPP Fellows pitched to win impossible challenges. Their answers were always terrifyingly accomplished.

Didn’t you have a stint as MD? What did you learn from that?

I was ‘volunteered’ to be managing director when we lost various Ogilvy and Mather officers in bizarre succession. There were 350 people in the agency. I quickly came to realise that some people are born to be managing directors and that, self-evidently, I wasn’t.

With draining company finances, I had to talk 25 people out of the door. That was horrible. My finance director, James Barnes Austin, was a pillar of strength and endlessly supportive. His safeguarding of what really kept the wheels going around was exemplary and, to a creative bloke like me, deeply humbling.

I benefited from his wisdom enormously. I also received capital-letter emails back from Martin Sorrell within minutes of sending him one, even if it was three in the morning. Most of all, I learned that, if you don’t attend to the creative work, your company will lose its soul in an instant.

You then moved on to Big Fish. What was your remit there? Any work you’re especially proud of?

Perry Haydn Taylor, the founder and inspirational leader of Big Fish, is a one-man powerhouse, but he needed to share the workload.

My remit at the Lots Road studio was to provide a second lane, as you find when cars wait for a ferry, so we could double up the creative projects nosing on board.

I found a concentration of talent, craft and skill I hadn’t seen since BBH days. We created and revivified a series of food and drink brands for the UK grocery trade.

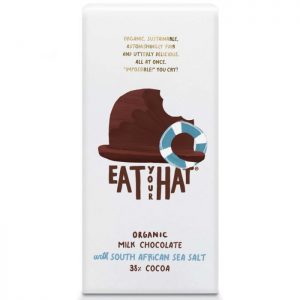

The work was exceptional. The designs will still be celebrated 100 years from now. Eat Your Hat, a Newcastle-based ethical grocery brand, was probably the most satisfying creation.

The work was exceptional. The designs will still be celebrated 100 years from now. Eat Your Hat, a Newcastle-based ethical grocery brand, was probably the most satisfying creation.

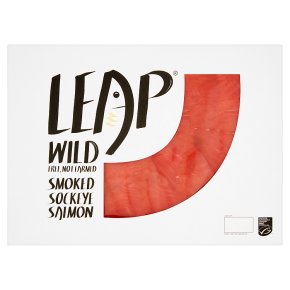

Leap and John Ross, two separate smoked fish brands now sitting in the chiller cabinet at Waitrose, were both, in different ways, deeply enjoyable projects.

I loved working with an apple brand in South Korea we christened Applekind. Our clients were a couple who saw their orchards as a way to soothe the industrial stresses of urban life. (Apples change hands for £10 each in the gift-giving culture of Korea.)

I also had something of an influence on Tyrrells crisps, as well as making minute contributions to both Yeo Valley and also Riverford’s communications. Latterly, Bertinet Bakery and Hain Daniels’ meat-free brand, The Incredible Alt, have arrived on shelf. There was never a dull Big Fish moment.

What’s your personal creative process?

Honestly, I’m not sure that I really have a creative process. It’s really about crowbarring enough space and time in which happy, imaginative accidents can happen.

With enough of a run-up, which is part time spent working, part experience and part luck, the final hop is often illogical, ill-defined and curiously unique. The hope is that one’s little leap fits the brief without being too clunky.

A good creative brief helps take you eighty per cent there. At Big Fish, this is condensed to one-line answers to five questions. (At BBH, it was six.) Everything that could help a copywriter or art director is covered:

- Why do you do what you do?

- Who (an individual) are you talking to?

- What do you want them to think, feel and do?

- How are you going to make them think, feel and do that?

- What does success look like?

The genius of simplicity. The relief of brevity. A recipe for success. That’s Perry for you.

Your old mucker Andrew Jolliffe caused quite a stir on here recently. What are your memories of him?

Andrew was an awkward heron of a creature when I met him, radiating benevolent, brilliant intelligence and possessed of a fantastic turn of phrase.

He was, and remains, a wonderfully sensitive copywriter. Somehow, he combines his own, distinct personality with chameleon-like dexterity to deliver uniquely fitting brand voices.

I picture him, grandiloquently, as a late Victorian hero who should be running down escarpments, tracking wildebeest from the top of an elephant, balancing a working gramophone on one knee and sipping dry sherry while he breaks several women’s hearts.

You couldn’t make him up. No film producer would allow it. He deserves to be cherished.

You’ve been around a while. How does creative work differ in 2020 from 1985?

When I joined the copywriting sandpit, the public quite liked ads. National tabloids covered its creation in slavish detail. We made a Levi’s commercial called Procession, which two newspapers devoted editorial spreads to covering.

With a chronically underfunded British film industry, the business saw talents that might have thrived more fully elsewhere blossoming in agency cultures.

Intelligence, warmth and dedication were poured into an advertising milieu that pumped out messages, through limited channels, in ways that stopped people rushing from the sofa to put the kettle on or turning over the page.

Here in 2020, competition for the audience’s eyes, ears and brains has multiplied a thousand-fold. The copywriter’s task is more challenging than ever. Success is now about overcoming time famine and attention deficit. The aim is still, as it ever was, to take out a long lease when renting space in people’s minds.

As a consequence, advertising as a general subject strikes me as being more shouty and less friendly. There isn’t time to develop communication beyond the purely functional in so many examples. It’s not wrong, but investment in brand personality has become the preserve only of the very deep-pocketed, or a tiny scattering of bold and brilliant companies.

When I started, copywriting on a good day was something like being a barrister. If I presented the truth well enough, the audience would readily absorb the message and often behave positively.

In 2020, it’s so much easier to be ignored. I feel it’s more like being a street newspaper seller, screeching at passers-by. Our local laundrette in West London has a yellowing sign in the window that says, ‘Our dry cleaning gets you noticed’.

I think that developing advertising that achieves that same result, without resorting to cheap, flashy tactics that backfire badly, is the hurdle to overcome.

There are still exemplary companies (and agencies) delivering joyful results. Look hard enough, you can always find some good stuff. I disagree profoundly with the tribe of splenetic old men who lurk on LinkedIn, insisting everything has gone to shit, in bitter barbs of Twitter-ish venom. They’re very tiresome.

Do you think clients get too locked into the idea that one particular type of media can solve all their problems?

The debate has always been about channel versus vehicle. It’s not really anything new, but the proliferation of channels has made the arguments even more strangled. The obsession is too often with the train tracks, not the locomotive. It’s the locomotive that people see and its impression is what stays with them.

TV is still remarkably resilient, even though we all skip through so many commercials. Moving image is where you can affect people’s opinions most profoundly. However, posters are now the last true mass-market broadcast medium.

In analogue or digital print, well-written, compressed prose can seal the deal in intimate ways that will make a consumer relationship deeper. Whichever the medium, in my mind, everything should start with a killer idea. Once there, you can debate whichever weapon you’ll use to deliver it till the cows come home.

How do you feel about the rise of social media?

Social media is like water. It irrigates just about everything in life but immerse your head into a bucket of the stuff for too long and you’ll drown. For a copywriter, it’s all about where, and how frequently, you play in the stream and ply your trade. Moderation in all things, if you like.

The most obvious point is that viewer choice determines the impact of engagement, not the advertiser’s weight of artillery. As a commercial writer, you have to tune up your emotional intelligence to ‘hear’ your subject’s reactions to keep them interested. The goal is to include them ‘in’ on the conversation, whether directly through the comment columns or, more usually, through empathetic inclusion. Social is a lean-in medium, not a sit-back one, and all the more interesting for it. Personally, I relish the challenges.

What’s your philosophy on pitching?

If you can avoid pitches, do. They don’t produce the best work. There was a statistic some years ago that less than 2% of pitch work actually runs. At the same time, you’re giving away free consultancy. Very rarely do clients pay for pitches.

It’s a one-hand clapping affair too where, maddeningly, you can’t see the competition. Honestly, though, given that it’s the worst system apart from all the others and exams are one of life’s necessary evils, I accept them as the drivers of the advertising world.

I’ve pitched well over 100 times. Happily, I’ve been with people who helped win more times than we lost.

My view, such as it is, is to ask questions of the client’s perspective. Very often, the pitch brief put out to competing agencies is not the one that will solve the problem. As with medicine, the critical start point is establishing the right diagnosis.

What exactly is the single exam question that needs answering? If the pitch brief is vague, I will ask for clarification. It that’s not forthcoming, the exercise starts to smell like a beauty parade.

At BBH, we never presented creative work at pitches. The same was true of Big Fish. In both places, the approach to the business challenge and the discussions we had with prospects were extremely creative, but we would never show finished ads or designs.

The logic was: how could we possibly point to an answer when we didn’t fully understand the problem? That attitude lost us many potential clients. ‘A principle isn’t a principle until it costs you money’ was practically tattooed on the foreheads of new business people in both Kingly Street and Lots Road.

Nevertheless, it consistently led to great work, deeper relationships and stronger commercial success on all sides.

As an individual or a company, the hardest lesson is not to give too much away at the pitch, tempting though it might be to secure the win. You’ll never get it back. It also becomes near impossible to establish a proper commercial relationship thereafter.

How do you react to client criticism?

I try not to take client criticism personally. Truthfully, though, as with all of us, I actually take it extremely personally and then try shake it off and meet the requests or comments. It helps to realise that, perhaps more often than not, the criticism is likely to prove correct.

There are many clients who have improved my work significantly. In other situations, I disagreed profoundly with the criticisms made. I was very taken with a recent distinction that Jim Carroll, the gifted planner who became BBH’s chairman, made between moaning and complaining.

The British moan to any and everybody except the perpetrator or architect of their misery. If, instead, they were to complain by confronting the person or authority who could actually change things, so much more would be achieved.

Client criticism is simply orchestrated complaining. The best way I’ve found to deal with it is always to talk it through with each other rather than read it. Both sides end up happier that way.

The way to ease the sandpapery moments in your client relationships is to get to know them better. The more time you spend chatting, the greater the trust you can build. You’ll be given more rope and more authority. At that point, the danger to avoid is throttling yourself with your own ego.

Who’s the best out-and-out copywriter you’ve worked with?

There are an awful lot of candidates and this is an impossible question. I’ll restrict myself to a quartet. I have to specify who I’ve worked ‘with’ and ‘for’.

- Barbara Nokes. (‘For’: she knocked a lot of nonsense out of me and rocket-boosted my copywriting education.)

- Tim Riley. (‘With’, because he was about three offices down the corridor at BBH. His turn of phrase was always so much better crafted than any of ours.)

- Lee Anderson. (‘With’, because he was the writer who gave Big Fish its indelible linguistic footprint with words that captivated the foodie tribe.)

- Tim Delaney. (‘For’, because he offered me a job and the fascination of working at one of very few British agencies ever run by a copywriter. Scalpel-sharp articulation, brutally but beautifully compressed.)

Any great industry books you can recommend?

Read me – Roger Horberry/Giles Lingwood. I should declare that Roger is a mate. Great copywriting help, captivatingly written.

Hey Whipple, Squeeze This – Luke Sullivan. The how-to ad person’s guide, channelled as a gumshoe detective thriller. A page-turner.

Hegarty on Advertising – Sir John Hegarty. Definitive. Obviously.

Eating the Big Fish (and other titles) – Adam Morgan. Even if you only let Adam’s seductive, illuminating anecdotes wash over you, you’ll come away a better writer.

Truth, Lies and Advertising – Jon Steel. An all-encompassing view of the business. Acute. Smart. Human. Essential.

We, Me, Them and It – John Simmons. Red Bull for tired writers.

A Burnt-Out Case – Graham Greene. Not an industry read, but Tim Delaney’s favourite book. Inspirational, pitch-perfect language.

The Sportswriter and Independence Day – Richard Ford. (David Abbott’s favourite writer. Nuff said.)

Bliss – Peter Carey. A ruthless ad-agency satire. Hauntingly memorable ideas.

Where do you see advertising going in the future?

Where do you see advertising going in the future?

I have no special X-ray specs when peering at the future. My sense is that advertising will go wherever people’s imaginations can travel. We should all be buying tickets now, mindful that clichés, whining, shouting, screaming and jabbing at our audience hasn’t worked to date.

Keeping it truthful and being very, very careful not to exploit, insult or ignore the issues and beliefs of the day will become ever more essential.

Any thoughts about hanging up your Mac?

When Lady Longford was asked if she’d ever thought of divorce, she replied, ‘Divorce never. Murder often.’ (She was married for 69 years.)

I’d happily slaughter this particular Mac as it appears to be powered by an emphysema-riddled parrot on a tricycle. But I don’t think I’ll ever divorce myself from jotting down, scribbling and attempting to articulate my thoughts in ways that involve a pencil, a pen or a keyboard and that don’t, immediately, involve a conversation with another human being.